Nearly four years ago, a 62 year old Asian man presented as a new patient for evaluation of blur in the left eye and pain in his left temple x1 day. He denied light sensitivity, history of shingles, history of oral ulcers. He had chickenpox as a child. He had a complicated ocular history in the 2-4 years prior to seeing me, that resulted in a phthisical right eye following several corneal transplants, glaucoma surgeries, and retinal detachments secondary to cytomegalovirus (CMV).

Medical history was remarkable for hypothyroidism following thyroid irradiation and gouty arthritis. The only medication he was taking was levothyroxine.

Uncorrected entering acuity was light perception right eye and 20/80 left eye. Best corrected vision was light perception right eye and 20/50 left eye. Pupil was not easily visualized right eye, but round and reactive to light left eye. Extraocular motility was normal in both eyes. Confrontation visual field was unable to be performed right eye and was normal left eye. Intraocular pressure (IOP) was 14mmHg in the right eye and measured to be 72 to 77mmHg in the left eye by Goldmann applanation tonometry. Slit lamp exam revealed phthisical right eye. Left eye was remarkable for 1+ microcystic edema and 1+ superficial punctate keratitis affecting left cornea, 2-3 cells per high powered field (cphpf) in left anterior chamber, combined nuclear and cortical cataract, a large optic nerve with 0.7 vertical and horizontal C/D ratio. Gonioscopy revealed angle open to ciliary body band with 1+ trabecular meshwork pigment, and no peripheral anterior synechiae in the left eye.

A drop of Simbrinza, Betimol, and Travatan Z were instilled in office, and 500mg acetazolamide was given to take by mouth. Ninety minutes after treatment was initiated, eye pressure was 52mmHg. In the left eye, patient was instructed to use 1 drop Travatan before bed; Betimol, 1 drop 2 times per day; and Simbrinza, 1 drop 3 times per day; and start 250mg Acetazolamide 4 times per day by mouth. Patient was asked to return in 1 day for a repeat pressure check.

At follow up, left eye vision was improved to 20/30, eye pressure was reduced to 10mmHg, but anterior chamber reaction had increased to 1+ cell. There were no keratic precipitates (KPs) on the cornea. Dilated fundus exam revealed normal vessels and retina without evidence of vasculitis or retinitis.

Diagnosis of viral iritis/trabeculitis was made with suspicion of CMV as viral agent. Differential diagnoses included viral iritis/trabeculitis from another herpesviridae family member (herpes simplex, herpes zoster, or Epstein-Barr Virus); Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) syndrome and sympathetic ophthalmia. There was no evidence of posterior segment involvement, no skin or hair depigmentation, although this can take several months after onset of acute phase of VKH, and iritis was non-granulomatous. Non-granulomatous iritis can be seen in the chronic phase of VKH, in the acute phase it is generally granulomatous. Sympathetic ophthalmia usually causes granulomatous iritis and most commonly occurs within days or weeks of injury. It is most common following non-surgical trauma, but it can occur following multiple ocular surgeries. Both VKH and sympathetic ophthalmia often develop inflammation of the posterior segment.

Durezol 1 drop 4 times per day in the left eye was added to the previous medications. The patient was asked to continue Acetazolamide for 4 additional days, then stop, and return in 1 week.

At the next exam, the iritis had resolved and the eye pressure was 8mmHg. Durezol was tapered to 2 times per day; the patient was asked to continue all glaucoma medications as previously prescribed and return in 2 weeks. At the follow up exam, there was a rare anterior chamber cell and eye pressure was 12mmHg. The patient was asked to continue Durezol, 1 drop 2 times per day for an additional week, then taper to 1 time per day (an alternative of Prednisolone acetate 1% 1 drop 2 times per day was sent to the pharmacy as a cheaper alternative once Durezol was gone); Simbrinza was discontinued, Betimol was to be continued until gone, and Travatan was continued. Patient was scheduled for follow up in 2 weeks. At the follow up, the patient was using Prednisolone 2 times per day, Travatan and Betimol. Betimol and Travatan were stopped.

Over the next 2 months the anterior chamber reaction ranged from very rare cell to 2-3cphpf. As the steroid was tapered, the eye pressure would rise to the level of mid-20s to 30. First taper rate was by 1 drop per day after each week, when eye pressure would rise, we would increase the steroid and slow down the taper. For example, the eye pressure became elevated once the prednisolone was tapered to 1 drop per week, so the dose was increased to 1 drop per day and then the taper was slowed to reduce by 1 drop per day every 2 weeks. The next time the eye pressure increased, the taper was slowed to monthly dose change; when the eye pressure increased again, the taper was slowed to a dosage change once every 3 months.

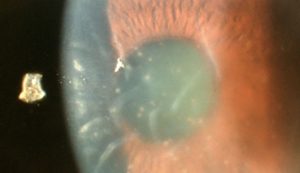

Over the first 3 years, the eye pressure would improve with an increase in steroids, but there came a point when eye pressure slowly began to rise, the cornea slowly developed keratic precipitates (KPs), the anterior chamber reaction slowly increased from 2-3 cphpf to 2+ cell. This occurred over several months. As the cell increased and the pressure increased, I would increase the dosage of the steroid. This seemed to keep the eye pressure in the high teens to low 20s range, but there was no longer an improvement in anterior chamber reaction. At one point, the patient was non-compliant with Durezol and returned with an eye pressure of 32mmHg and a complaint of blur. The cornea was swollen (eg: see photos 2 & 3). Increasing the steroid to 1 drop Durezol every 2 hours did not improve the findings or the symptoms of blur. Best corrected vision had dropped from 20/15 to 20/50+. The patient also started to notice intermittent new floaters. The KPs started to take on an unusual shape. Some were formed into small rings, or coin shapes with adjacent guttata (eg: see photos 1 & 3).

At first it was unclear if the cornea had become swollen due to an eye pressure spike or if there had been a change in the etiology, however, the swelling continued to worsen even as the eye pressure improved with more consistent steroid use and glaucoma medications . Uncorrected vision dropped to 20/100.

The fact that the signs and symptoms were worsening despite the usual treatment was evidence that something had changed. The etiology was no longer an inflammatory response to viral particles as is the case in viral trabeculitis, but active viral infection attacking the corneal endothelial cells. The corneal edema was caused by CMV keratouveitis. In my research into this disease, I discovered that coin shaped KPs are pathognomonic for CMV endotheliitis.

I started the patient on Zirgan 1 drop every 2 hours along with continuing Durezol every 2 hours. Patient also continued using glaucoma medications. We discussed starting Valcyte but we had tried this medication in the past to see if it would allow for taper off steroid eye drops, but it was very expensive and the patient was unwilling to pay for it again.

I found a small study that looked at the effectiveness of reducing viral load using 2g Valacyclovir, 4 times per day in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients1. It seemed to have good results. I discussed starting this high dose of medication with the patient’s PCP and discussed having the PCP monitor for kidney function. Kidney function testing came back normal. Patient was started on 2gm Valacyclovir 4 times per day by mouth and 1gm L-Lysine 3 times per day by mouth. After 2.5 weeks on Zirgan, and 1.5 weeks on high dose Valacyclovir the corneal edema started to clear and uncorrected vision returned to 20/30-2. At last exam, the corneal edema was completely gone. I reduced Zirgan to 5 times per day and Durezol to 4 times per day. I plan to continue present management until the KPs have resolved, then slowly taper, but likely leave him on Zirgan bid, indefinitely2.

Cytomegalovirus is a member of herpesviridae. Herpesviridae viruses are known to cause high eye pressure spikes due to inflammation of the trabecular meshwork and physical blockage of the trabecular meshwork by inflammatory cells. CMV more commonly affects those that are immune compromised, but it can affect immune competent patients. There may be a higher prevalence of CMV endotheliitis in immunocompetent Asian men6. The KPs will often be coin-shaped or linear and pseudo-guttata may be present. Findings can mimic corneal transplant rejection. Herpes simplex can also cause viral endotheliitis. PCR can be performed on aqueous fluid from an anterior chamber tap to differentiate the two and to monitor for treatment response.

Endotheliitis may respond to either oral or topical antiviral treatment, but seems to respond best to a combination of both. The most efficacious oral antiviral for CMV keratouveitis is Valcyte (valganciclovir). Typical dosing is 450mg to 900mg twice daily for 6 weeks, then once daily. This drug can be very expensive. Valganciclovir is the prodrug of ganciclovir which means it is converted into ganciclovir in vitro. This is why I placed the patient on Zirgan (ganciclovir) gel as opposed to trifluridine; Zirgan is also much gentler to the ocular surface when compared to trifluridine.

There is a small amount of controversial evidence that the amino acid L-Lysine (Lysine) may reduce the severity and frequency of herpes simplex outbreaks by interfering with viral replication. There is less research as to if it is able to reduce CMV replication, but I did find a small study that suggests that it may. Lysine is generally well tolerated with a low side effect profile. The studied dosages for herpes simplex are 1gm once per day to three times per day. While there is not a lot of research on the effect Lysine may or may not have on herpesviridae viral replication, the risk of starting such a well tolerated supplement was very low, so in this case, I decided to have the patient start the supplement.

CMV endotheliitis can be difficult to diagnose and treat. Most people are carriers of the dormant virus. It should be considered as a differential diagnosis in patients with corneal edema and a history of elevated eye pressure, glaucoma, or corneal transplant.

PHOTO 1

DOI: 10.3341/kjo.2013.27.2.130

PHOTO 2

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.07.057

PHOTO 3

https://www.eyeworld.org/article-diagnosing-and-treating-cmv-anterior-uveitis-and-endotheliitis

References:

- Shin-Yeu Ong, Ha-Thi-Thu Truong, Colin Phipps Diong, Yeh-Ching Linn, Aloysius Yew-Leng Ho, Yeow-Tee Goh & William Ying-Khee Hwang. Use of Valacyclovir for the treatment of cytomegalovirus antigenemia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. BMC Hematology volume 15, Article number: 8 (2015).

- Pavan-Langston, Deborah et al. Ganciclovir Gel for Cytomegalovirus Keratouveitis. Ophthalmology, Volume 119, Issue 11, 2411. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.024

- M. Hosoya,1,2 J. Neyts,2 N. Yamamoto,” D. Schols,2 R. Smoeck,2 R. Pauwels2 and E. De Clercq2* 1Department of Microbiology, Fukushima Medical College; Fukushima, Japan. 2Rega Institute for Medical Research, Minderbroedersstraat 10, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium. Inhibitory effects of polycations on the replication of enveloped viruses (HIV, HSV, CMV, RSV, influenza A virus and togaviruses) in vitro. Antiviral Chemistry & Chemotherapy (1991) 2(4), 243-248

- Kitazawa K, Jongkhajornpong P, Inatomi T, et al. Topical ganciclovir treatment post-Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty for patients with bullous keratopathy induced by cytomegalovirus. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2018;102:1293-1297.

- Koizumi N, Miyazaki D, Inoue T, et al. The effect of topical application of 0.15% ganciclovir gel on cytomegalovirus corneal endotheliitis. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2017;101:114-119.

- Kumar, A. & Mehta. Diagnosis and Management of CMV Endotheliitis. J.S. Curr Ophthalmol Rep (2019) 7: 98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40135-019-00205-0

- Koizumi N, Inatomi T, Suzuki T for the Japan Corneal Endotheliitis Study Group, et al. Clinical features and management of cytomegalovirus corneal endotheliitis: analysis of 106 cases from the Japan corneal endotheliitis study. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2015;99:54-58.

- Choi WS, Cho JH, Kim HK, Kim HS, Shin YJ. A Case of CMV Endotheliitis Treated with Intravitreal Ganciclovir Injection. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2013 Apr;27(2):130-132. https://doi.org/10.3341/kjo.2013.27.2.130

Author: Davina S. Kuhnline, OD

Sequim Clinic

I chose to share this case because it has taught me a lot over the last few years. While CMV is rarely a cause of ocular disease in immunocompetent patients, it is a member of the herpesviridae family and the treatment considerations are similar to ocular disease caused by herpes simplex and zoster which are much more common. I enjoy working with you to help manage these challenging and unusual cases.